If you pull on the thread for

long enough, the whole thing unravels.

Piermont, New York Mayor

Bruce Tucker is currently in the middle of a New York State Comptroller “Risk

Assessment” scrutinizing his and the Village’s mishandling of resident taxpayer

dollars and finances. The Comptroller’s “Risk Assessment” is the traditional

precursor to a plenary Comptroller audit. That’s now well-known throughout the

2,500-person village.

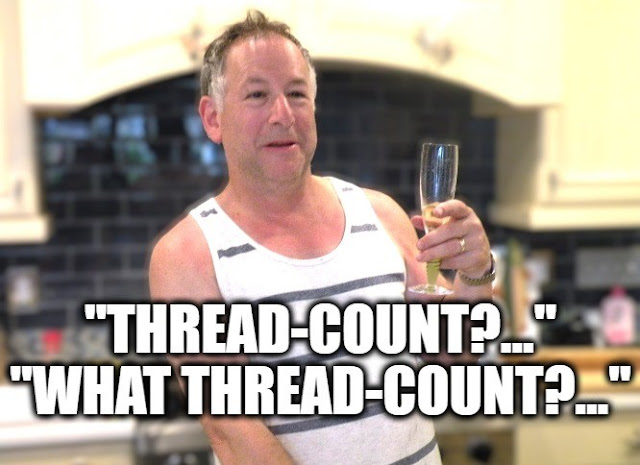

What is astounding, though,

is how little the Piermont, New York electorate and others actually know, to this day,

about Bruce Tucker and his sordid past history as a sheet and towel salesman

with Elizabeth, New Jersey-based “Rainbow Linens, Inc.”

Well, all that is about to

change. Effective now.

https://unhandpiermont.blogspot.com/2024/11/the-next-mayoral-conference-should-be.html

https://x.com/UPiermont57293/status/1862974918373118362

https://unhandpiermont.blogspot.com/2024/11/the-next-mayoral-conference-should-be.html

https://x.com/UPiermont57293/status/1862974918373118362

Below you can read the Year

2006 Wall Street Journal article, also picked-up in the Atlanta Constitution, explaining

how, in his former garmento life in the “sheeting business”, now-Mayor Bruce

Tucker actually falsified the thread-counts of his “Rainbow Linens”

sheets wholesaled to retailers.

He then got busted by the

Wall Street Journal, by the Atlanta Constitution, and by Hearst’s “Good

Housekeeping Research Institute” for it… Actually busted by “Good Housekeeping”!… That

would be like getting thrown-out of a backstage hang with Ambrosia.

The more things change, the

more they stay the same. Up to now, Piermont residents have wondered how they

could have elected and re-elected a Mayor who, as his unsavory and unscrupulous

“pet project”, propagated a fake zoning law, to enable a corrupted real estate development

at 447-477 Piermont Avenue - while he lied about its environmental impacts, and

while he recklessly put the Village of Piermont into a deep financial black

hole by dint of his rank fiscal mismanagement otherwise.

Yet the answer was hiding in

plain sight all the time. It’s right there in the Wall Street Journal. He is

the same Bruce Tucker now, as he was then. He lied to his retailer customers

and the purchasing public then. And he lies to his Piermont constituents now. Meet

the Recidivist Garmento out of Elizabeth, New Jersey – your very own hometown Mayor,

none other than one Bruce Edward Tucker.

Now pull on that thread, and

demand Bruce Tucker’s resignation and permanent removal from office. Here are some FOIA demands to start things off:

The text of the Wall Street Journal article from Year 2006,

follows below in Word format:

https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB116052613652288766

Good Housekeeping Touts Its Test Lab To Seek New Readers’ Seal of Approval.

By Sarah Ellison

Oct. 11, 2006 12:01 am ET

The research arm of Good Housekeeping magazine has been testing products for more than a century and granting advertisers who pass muster its famous seal of approval for almost as long. In its early days, the magazine’s “experiment station” was designed to help new brides become better housekeepers.

The Hearst Corp. magazine has evolved since then, but it is its testing lab -- now called the Good Housekeeping Research Institute -- that has undergone the biggest facelift of late as the magazine pushes to maintain its position among traditional women’s titles while fending off arriviste like Martha Stewart Living, Real Simple and O, The Oprah Magazine.

[Testing a dress in the 1940s].

Good Housekeeping, with a circulation of 4.6 million, still has more than double the audience of the newer entries but has been losing readers over the years. Circulation is down nearly 25% since the late 1960s, and 11% since 1995.

The institute and its gleaming 20,000-square-foot headquarters on the 29th floor of Hearst’s new midtown Manhattan building will be part of a push to tout Good Housekeeping’s product testing, serving as the backdrop for the magazine’s regular segments on ABC’s “Good Morning America” and NBC’s “Today.” It will be the most visible sign of the magazine’s efforts in recent years to emphasize its research -- including expanding its work beyond issuing the seal of approval to qualified advertisers to rating products from linens to washing machines.

“I think we can use it more,” says Rosemary Ellis, who was named the magazine’s editor-in-chief in May, replacing longtime editor Ellen Levine, who became editorial director for all Hearst magazines.

The Good Housekeeping Seal famously promises that if a product proves defective within two years of purchase, Good Housekeeping will offer a refund to anyone who requests it. To advertise in the magazine, a product needs to qualify for the seal. Likewise, to get the seal, a product has to advertise in the magazine, which some say hurts the seal’s credibility as an objective measure of quality. Consumer Reports, for instance, doesn’t accept advertising, and has an extensive testing lab. It doesn’t offer a refund, though, to unhappy consumers.

Good Housekeeping defends the seal. “It’s a money-back guarantee,” says Publisher Patricia Haegele. “We have to be able to back it up, and the process is even more deliberate because of that when it comes to putting a seal on the product.”

[The seal of approval today].

But the seal had lost its relevance with younger consumers. “The seal still gives consumers confidence, but for people between the ages of 18 and 34 who didn’t grow up with grandma and grandpa’s Good Housekeeping seal, they’re not really sure what it means,” says Burt Flickinger, a marketing and retail consultant and managing director of Strategic Marketing Group in New York.

As much as the Good Housekeeping Seal became a household name throughout the last century, the testing lab behind it remained relatively unknown. That is, until Ms. Levine gave the researchers who staff the institute a broader mandate: Instead of just testing products and making sure they were safe to be advertised, she urged staffers to do their own research, to sniff out faulty products or consumer frauds that she could expose in the magazine, regardless of whether the products were advertised in Good Housekeeping. “We urged them to become reporters,” says Ms. Levine.

[The institute tests a variety of products, including stuffed animals].

Now, says Ms. Ellis, “They are all like a dog with a bone.” One of the most zealous is Kathleen Huddy, director of the institute’s textiles laboratory. Every day, Ms. Huddy tortures fabrics, rubbing rough metal over them to encourage fraying, pulling on them to see if they’ll tear and setting them on fire.

In 2002, she did her first towel investigation and found that many towel manufacturers added a softener to the finished product which makes the unwashed towel feel softer in the store. It also helps the towel hold its shape for a few washes. However, after being washed repeatedly (Ms. Huddy’s test includes 25 washes) the towel lost its softness and shrunk.

In its October issue that year the magazine ran an article telling readers, “Towels: Don’t fall for the fluff.” In it, the “biggest loser” was Martha Stewart’s Everyday Egyptian towel because it shrunk almost six inches after repeated washes. A spokeswoman for Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia Inc. said the company did its own tests and found Good Housekeeping overstated the amount of shrinkage.

Ms. Huddy followed up on her research earlier this summer and concluded that many manufacturers have stopped using the softener and have increased the size of their towels by two inches. She picked Kohl’s Sonoma brand as her favorite for “fade resistance” and avoiding shrinkage.

After the initial towel tests, Ms. Huddy turned her attention to sheets. She had noticed sheet sets on sale for $169.99 that claimed an 800-thread count. But by looking at the sheet fibers under a microscope and counting the number of threads per square inch, she discovered that some manufacturers, such as Synergy and Rainbow Linens Inc., were counting the individual plies that make up each of the threads in the thread-counts, thereby doubling the actual number. A follow-up earlier this year found similar problems with other brands, including Synergy.

Bruce Tucker, Rainbow’s owner, says his company now only use single-ply threads, but it had nothing to do with the institute’s findings. Synergy did not return calls seeking comment.

In Hearst’s new corporate headquarters, which officially opened earlier this week, the institute gets a whole floor. It houses 15 employees as well as multiple test kitchens and labs, a climatology chamber to expose products to extreme temperatures, a soundproof room and updated equipment to test things ranging from the durability of stuffed animals to the effect of moisturizers on human skin.

The first thing visitors to the newly revamped institute see when they walk through the glass doors is a white wall with a red line slashed through the middle of it. Above the horizontal line are “good” products, those that have earned the Good Housekeeping Seal. Below is a kind of hall of shame of products such as a princess dress that easily caught on fire or a “fake fitness belt,” a vibrating belt that was designed to help a user lose weight but burned some people instead.

Write to Sarah Ellison at sarah.ellison@wsj.com

https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB116052613652288766

Good Housekeeping Touts Its Test Lab To Seek New Readers’ Seal of Approval.

By Sarah Ellison

Oct. 11, 2006 12:01 am ET

The research arm of Good Housekeeping magazine has been testing products for more than a century and granting advertisers who pass muster its famous seal of approval for almost as long. In its early days, the magazine’s “experiment station” was designed to help new brides become better housekeepers.

The Hearst Corp. magazine has evolved since then, but it is its testing lab -- now called the Good Housekeeping Research Institute -- that has undergone the biggest facelift of late as the magazine pushes to maintain its position among traditional women’s titles while fending off arriviste like Martha Stewart Living, Real Simple and O, The Oprah Magazine.

[Testing a dress in the 1940s].

Good Housekeeping, with a circulation of 4.6 million, still has more than double the audience of the newer entries but has been losing readers over the years. Circulation is down nearly 25% since the late 1960s, and 11% since 1995.

The institute and its gleaming 20,000-square-foot headquarters on the 29th floor of Hearst’s new midtown Manhattan building will be part of a push to tout Good Housekeeping’s product testing, serving as the backdrop for the magazine’s regular segments on ABC’s “Good Morning America” and NBC’s “Today.” It will be the most visible sign of the magazine’s efforts in recent years to emphasize its research -- including expanding its work beyond issuing the seal of approval to qualified advertisers to rating products from linens to washing machines.

“I think we can use it more,” says Rosemary Ellis, who was named the magazine’s editor-in-chief in May, replacing longtime editor Ellen Levine, who became editorial director for all Hearst magazines.

The Good Housekeeping Seal famously promises that if a product proves defective within two years of purchase, Good Housekeeping will offer a refund to anyone who requests it. To advertise in the magazine, a product needs to qualify for the seal. Likewise, to get the seal, a product has to advertise in the magazine, which some say hurts the seal’s credibility as an objective measure of quality. Consumer Reports, for instance, doesn’t accept advertising, and has an extensive testing lab. It doesn’t offer a refund, though, to unhappy consumers.

Good Housekeeping defends the seal. “It’s a money-back guarantee,” says Publisher Patricia Haegele. “We have to be able to back it up, and the process is even more deliberate because of that when it comes to putting a seal on the product.”

[The seal of approval today].

But the seal had lost its relevance with younger consumers. “The seal still gives consumers confidence, but for people between the ages of 18 and 34 who didn’t grow up with grandma and grandpa’s Good Housekeeping seal, they’re not really sure what it means,” says Burt Flickinger, a marketing and retail consultant and managing director of Strategic Marketing Group in New York.

As much as the Good Housekeeping Seal became a household name throughout the last century, the testing lab behind it remained relatively unknown. That is, until Ms. Levine gave the researchers who staff the institute a broader mandate: Instead of just testing products and making sure they were safe to be advertised, she urged staffers to do their own research, to sniff out faulty products or consumer frauds that she could expose in the magazine, regardless of whether the products were advertised in Good Housekeeping. “We urged them to become reporters,” says Ms. Levine.

[The institute tests a variety of products, including stuffed animals].

Now, says Ms. Ellis, “They are all like a dog with a bone.” One of the most zealous is Kathleen Huddy, director of the institute’s textiles laboratory. Every day, Ms. Huddy tortures fabrics, rubbing rough metal over them to encourage fraying, pulling on them to see if they’ll tear and setting them on fire.

In 2002, she did her first towel investigation and found that many towel manufacturers added a softener to the finished product which makes the unwashed towel feel softer in the store. It also helps the towel hold its shape for a few washes. However, after being washed repeatedly (Ms. Huddy’s test includes 25 washes) the towel lost its softness and shrunk.

In its October issue that year the magazine ran an article telling readers, “Towels: Don’t fall for the fluff.” In it, the “biggest loser” was Martha Stewart’s Everyday Egyptian towel because it shrunk almost six inches after repeated washes. A spokeswoman for Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia Inc. said the company did its own tests and found Good Housekeeping overstated the amount of shrinkage.

Ms. Huddy followed up on her research earlier this summer and concluded that many manufacturers have stopped using the softener and have increased the size of their towels by two inches. She picked Kohl’s Sonoma brand as her favorite for “fade resistance” and avoiding shrinkage.

After the initial towel tests, Ms. Huddy turned her attention to sheets. She had noticed sheet sets on sale for $169.99 that claimed an 800-thread count. But by looking at the sheet fibers under a microscope and counting the number of threads per square inch, she discovered that some manufacturers, such as Synergy and Rainbow Linens Inc., were counting the individual plies that make up each of the threads in the thread-counts, thereby doubling the actual number. A follow-up earlier this year found similar problems with other brands, including Synergy.

Bruce Tucker, Rainbow’s owner, says his company now only use single-ply threads, but it had nothing to do with the institute’s findings. Synergy did not return calls seeking comment.

In Hearst’s new corporate headquarters, which officially opened earlier this week, the institute gets a whole floor. It houses 15 employees as well as multiple test kitchens and labs, a climatology chamber to expose products to extreme temperatures, a soundproof room and updated equipment to test things ranging from the durability of stuffed animals to the effect of moisturizers on human skin.

The first thing visitors to the newly revamped institute see when they walk through the glass doors is a white wall with a red line slashed through the middle of it. Above the horizontal line are “good” products, those that have earned the Good Housekeeping Seal. Below is a kind of hall of shame of products such as a princess dress that easily caught on fire or a “fake fitness belt,” a vibrating belt that was designed to help a user lose weight but burned some people instead.

Write to Sarah Ellison at sarah.ellison@wsj.com